BILL CLEMENTS: A TEXAS LIFE

Bill Clements at his family ranch near Forney, TX ca. 1978

When political currents begin to shift, the earliest signs are often mistaken for aberrations. As it was happening, and even for a long time afterward, the 1978 Texas gubernatorial election seemed the very definition of a political anomaly. The Texas Democrats had long controlled every lever in the machinery of the state’s government, and no Republican had resided in the Governor’s Mansion in over 100 years. A prominent and widely respected Democrat like state attorney general John Hill should, as a matter of course, have demolished any Republican nominee. His opponent for the cycle was a wealthy, gaffe-prone political novice named William Clements. Early polling gave Hill a three-to-one lead against the little-known Republican.

But Bill Clements was nothing like the candidates the Texas Republicans usually fielded in the governor’s race. Founder of one of the world’s largest oil drilling companies and former Deputy Secretary of Defense, Clements was a formidable man. He had already spent an unprecedented $1.8 million to secure the Republican nomination, and was poised to set new spending records in the general election. Clements’ gubernatorial campaign was thus unusually sophisticated for a state race, employing the latest techniques in poll tracking and targeted advertising.

Nor was 1978 a typical election year. Like the rest of the nation, Texas was in the midst of profound transformation—economically, demographically, and politically. With change came opportunity. Contrary to history, polling data, and the collective wisdom of the Texas punditry, Clements and his advisors not only believed he could win, but that his victory might pave the way for a major party realignment in the state.

Clements’ victory that year genuinely shocked most Texas political observers. His almost cartoonish self-confidence—mocked roundly during the campaign—now seemed strangely clairvoyant. What to make of this man? The simple patterns of speech, categorical assertions and reflexive abrasiveness—all elements of Clements’ quintessential “Texan-ness”—hardly seemed to fit with his exceptionally accomplished and actually quite cosmopolitan background. Yet there was rarely any hint of pandering in Clements’ public interactions. In business, he had been blunt, domineering, and utterly effective. And that’s precisely how he sold himself to Texas voters in 1978: as “a businessman, not a politician.”

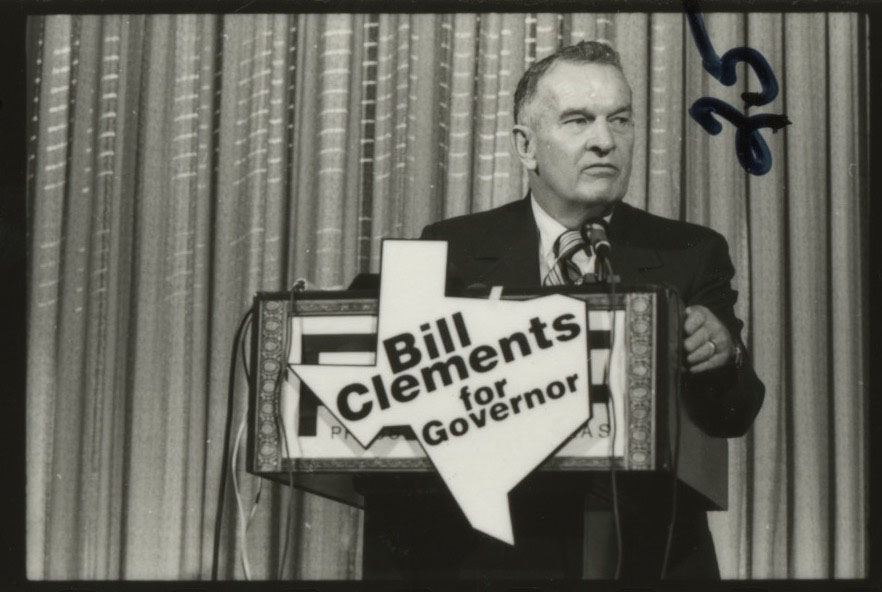

Clements on the campaign trail in 1978

Not coincidentally, Bill Clements was also a fiercely proud Texan. As his biographer Carolyn Barta noted, the trajectory of his life and career mirrored that of a changing Texas. He had made his name and fortune in a rural, single-party state dominated by a handful of industries, and in terms of personal style, he never strayed from his roots as plain-speaking Texas roughneck. In fact, much of Clements’ political appeal lay in his artless evocation of Texas’ mythical past. Yet as governor, he steered his beloved state through a dizzying era of modernity, from urbanization and economic diversification to political realignment and policy reform. During his two non-consecutive terms as governor, from 1978 to 1982, and then again from 1986 to 1990, Texas conservatives began leaving the Democratic Party, laying the foundation for the 1990s Republican ascendency. In retrospect, this confluence of man and moment in 1978 did indeed represent a clear turning point in the history of modern Texas politics. And like most things involving Bill Clements, none of it was accidental.

MAKING GOOD: EARLY LIFE, BUSINESS AND POLITICAL AWAKENING

Bill Clements ca. 1933, he played guard for the Highland Park High School football team.

Oil—and Texas' boom-and-bust oil industry—were woven into the fabric of Bill Clements' early life. He was born in 1917 in Highland Park, a wealthy enclave of Dallas. His father Perry Clements had once been a small-time lease broker in the North Texas oilfields. Young Bill came of age during the discovery and development of the vast East Texas Oil Field, which made the fortunes of a number of his family's Highland Park friends during the early 1930s. Those who knew him as a youngster recalled an affable and popular boy who was driven to succeed at anything he undertook, especially scouting and football. In 1934, Perry Clements informed his son that he was broke, and that Bill would not be following his friends to college. The younger Clements absorbed the setback in stride, adjusted his expectations, and set off instead for the South Texas oilfields to help support his family.

As it turned out, the rigors of drilling work agreed with Bill Clements, lending shape and direction to his outsized ambitions. Although he later attended a few years of college at SMU and UT Austin, Clements ultimately returned to the oil patch without a diploma—or regrets. Roughnecking, he would say later, was "like getting a Ph.D. in life." Fascinated by the mechanics of the drilling rigs themselves, he worked at servicing them for a major drilling equipment manufacturer along the Gulf Coast. In 1947, Clements found an investor to stake him for two used rigs and went into business for himself, founding an oil-drilling contracting company called the Southeast Drilling Company, or SEDCO. From then on, his vision and hard-driving leadership propelled and sustained SEDCO's expansion and innovation. The company grew steadily in its early years, but the introduction of its Series 135 drilling rig in 1965 cemented SEDCO's status as a leader in the booming offshore drilling industry. By the late 1960s, Clements was a millionaire many times over, and SEDCO's Dallas headquarters housed one of the largest and most capable oil drilling companies in the world.

Clements and unidentified men on a drilling rig, undated, courtesy of William P. Clements, Jr. Records, Cushing Library, Texas A&M University

Dallas also served as Bill Clements' springboard into public life. As Dallas' wealthiest citizens grew in both affluence and influence after World War II, they were impatient to bring their city's unique brand of conservative ideology to state and even national politics. The Dallas Citizens Council—an exclusive directorate of corporate and civic elites, and the city's most powerful civic body—tapped Clements to serve as its director in 1960. Through the Citizens Council, Clements immersed himself in local philanthropy and politics. Like most right-leaning Texans of the era, he considered himself a political independent: a ticket-splitter who generally backed conservative Democrats in state elections and Republicans in national races. But his close friend Peter O'Donnell, a Dallas banker whose work on behalf of the Texas Republican Party dated to the 1950s, believed that a man like Clements could help reverse Republican fortunes in the state. O'Donnell convinced Clements to raise money for George Bush's losing 1964 Senate bid, and then for Richard Nixon's 1968 presidential campaign. Freed somewhat from the day-to-day duties of running SEDCO, Clements poured more and more of his time and energy into Republican fundraising.

Bill Clements' rise in the Dallas political firmament was characteristically spectacular, and by 1972, he had become a bona fide power broker in the Texas Republican Party. He'd supported Nixon again that year—this time as the campaign's Texas co-chair—where he met many of the people who would later work for him as governor, as well as his future second wife, Rita (who was married to Texas resort magnate Dick Bass). Clements' arc suggested an imminent run for a public office of his own, but in December of that year, Richard Nixon instead nominated him as Deputy Secretary of Defense. Clements was a controversial choice. His outspoken advocacy for increased military spending and buildup was out of step with prevailing defense doctrine in the immediate post-Vietnam era. As Deputy Secretary moreover, Clements would be responsible for the Pentagon's entire budget, and SEDCO's considerable interests overseas posed potential conflicts of interest. Nevertheless, Clements won confirmation over the objections of a number of prominent Democrats. Entrusting the leadership of SEDCO to his son Gill, he came to Washington in early 1973 to manage the day-to-day operations and budget of one of the largest and most complex organizations in the world.

Courtesy of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library

Clements spent four years in Washington—a period that spanned the fall of Saigon, the Yom Kippur War, Watergate, and the ongoing SALT talks. Despite his lack of military experience, he quickly earned a reputation as a skillful administrator and bureaucratic in-fighter. As Deputy Secretary, Clements focused on weapons procurement, forging closer ties between the Pentagon and defense contractors, and selling advanced armaments to American allies overseas. He recruited other high profile business leaders to serve in the Pentagon, and championed a number of weapon and sensor systems that would become frontline mainstays for the American armed forces through the 1980s and 90s. While in Washington, he married Rita Crocker, to whom he had grown closer since their first meeting in 1972. With the election of his ideological nemesis, Jimmy Carter, as president in 1976, Clements went home to Dallas and SEDCO.

BREAKING THROUGH: 1978 CAMPAIGN AND FIRST TERM

Bill and Rita Clements in front of the Texas capital building, 1978.

Upon his return to Texas, Bill Clements found it difficult to readjust to his old life. His son Gill had steered SEDCO quite capably in his absence, and Bill's time in Washington had only deepened his confidence in his own capacity for leadership. He was restless, and in search of another challenge. According to Carolyn Barta, Bill and Rita Clements decided together that he would run for governor of Texas in November of 1977. The daughter of an activist in Depression-era Kansas, Rita was a natural political adept, with a keen sense of how to compete in the singular world of Texas politics. On a list of pros and cons Rita drew up, "pros" included Clements' sense of responsibility to "give back" to his state, his ability as a leader, and their shared sense that the race was "winnable." She also listed, "supporting wife." But Rita was more than just supportive; from then on, she became his most trusted and influential political advisor.

The list of pros did not include Clements' ability to personally finance a large campaign, although perhaps it should have. In the end, Bill Clements spent $7 million of his own money to get elected in 1978. Many in the Republican Party had seen it as a rebuilding year, but from the outset, Clements declared that he wasn't merely running for the experience, and that he expected to win. After making the decision, they informed Clements' friend and confidant Peter O'Donnell, who quickly set about assembling the team that would put Clements into the Governor's Mansion just a year later.

Inauguration, 1978. From the Prints and Photographs Collection, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, #1980/68-23.

In 1978, Bill Clements came to office intent on slashing budgets, cutting taxes, and reorganizing Texas' sprawling and inefficient state bureaucracy to run more like a business. It was a radical and ambitious agenda aimed straight at the heart of Democratic power in state politics, which relied on a spoils system to preserve its power and keep members in line. In addition, the governor-elect brought with him a decidedly top-down conception of executive power, honed by his experiences as a CEO and Pentagon executive. He was unpracticed at building consensus, and had yet to learn the limits inherent to his new office. The stage was thus preset for a clash between Clements and the still overwhelmingly Democratic Texas legislature.

Indeed, within the first few months of his term, the new governor found himself on the receiving end of the first gubernatorial veto override by the Texas legislature in almost 40 years. Chastened, Clements quickly realized that a Texas governor simply didn't have the clout to take on a hostile legislature and state bureaucracy at the same time. There wasn't much he could do about the legislature—at least not right away. But he could certainly do something about the bureaucracy. Through prodigious appointments and the creation of countless task forces, advisory councils and committees, Clements swung the proverbial fire hose of state patronage toward his own friends, backers and party. In so doing, he began to reshape the state's bureaucracy in the image of his party, and to recruit ambitious young Texans to the Republican brand. Among them was a political operative named Karl Rove.

Although he had campaigned in 1978 as a conservative firebreather, Bill Clements' political instincts were those of a businessman, not a zealot. Even amidst the fiercest clashes with opponents, he rarely resorted to political hostage taking, and improved markedly over the course of his first term at building consensus behind pragmatic approaches to difficult issues. In his first term, Clements slowed the growth of state government, instituted a number of tax reforms, and commissioned a major study to prepare for the state's economic future. He instituted management-by-objective techniques borrowed from the business world to increase productivity and accountability within the state's bureaucracy. He became a leading proponent of the emerging national policy consensus around the "war on drugs," and made Texas a proving ground for drug prohibition and criminalization. His administration also moved aggressively to improve the state's relations with neighboring Mexico, and under Rita's leadership, renovated the Governor's Mansion.

Gov. Clements' first term was not without its political headaches. He was panned for his dismissive comments when Ixtoc 1—an offshore rig owned by SEDCO—suffered a blowout and spilled millions of gallons of oil into the Bay of Campeche in 1979. In 1980, Judge William Wayne Justice ruled for the plaintiff in Ruiz v. Estelle, who had argued that his treatment in Texas prisons was unconstitutional. Having vetoed any new money for prisons in that year's budget, Gov. Clements was forced to ask the legislature for additional funding to build new prisons in order to reduce overcrowding. There were sharp skirmishes over redistricting, as well as the relatively low numbers of minority appointees coming out of the Governor's office.

Still, Gov. Clements' prospects for reelection in 1982 seemed bright. His opponent was sitting Texas Attorney General Mark White, who was widely seen as a competent but uninspiring candidate. But Clements' poor relationship with the press, coupled with the so-called "Reagan recession" in 1982, helped make the race unexpectedly competitive. Thanks to Clements' own gaffes and campaign missteps, the campaign turned into a referendum on his personality and leadership, making his unexpected loss to White that much more painful. After leaving office, Bill Clements retreated back into philanthropic work in Dallas, and soon accepted the chairmanship of Southern Methodist University's Board of Governors.

A RETURN: THE SECOND TERM

Courtesy of Briscoe Center for American History

Despite his hard-won victory, Mark White encountered a number of headwinds as governor. The state's economy languished under his watch, oil prices collapsed, the budget situation was dire, and his education reforms turned out to be deeply unpopular. As an incumbent, White was vulnerable—particularly to a well-known Republican. But Clements was initially wary of a 1986 rematch. He'd been beaten once, and many on the Republican side believed the surging GOP would be better served by a fresher, younger candidate. Still, the prospect of defeating the man who'd bested him in '82 was immensely appealing, and initial polling suggested that Clements would do well against his old adversary. He reassembled his trusted advisors, including Peter O'Donnell and Karl Rove, and launched his campaign in July of 1985.

Bill Clements had changed in the years since his loss to White in 1982. The old fire and haughtiness remained, but now they were tempered by an approachability and composure that hadn't been there before. The change was born out by Clements' relationship with the political press on the 86' campaign trail, which was as cordial and warm as it had been acrimonious when he was governor. Clements kept the focus on job creation, limited his own mistakes on the stump, and won the election with just under 53% of the popular vote.

Upon taking office, Clements moved quickly to stabilize the state's budget crisis, and met with Judge Justice to hammer out the final terms of the Ruiz decision. But within weeks, his new administration was knocked off-course by the worst crisis Clements had faced as a public figure: the scandal that came to be known as Ponygate. Days after Clements' victory, a Dallas news station aired an investigative report alleging that Southern Methodist University football players were being paid through a slush fund established by a school booster—a grave violation of NCAA rules. The revelation touched off a wave of resignations, including that of the university's president.

After conducting its own investigation, the NCAA took the unprecedented step of giving SMU the "death penalty" for its recruiting violations, which included banning its football program from competition for one year, along with several additional sanctions. Clements, it was soon revealed, had learned of the secret player payments after becoming Chair of the Board of Governors. Looking for a way out of the mess he'd inherited, Clements had argued for a gradual phase-out of SMU's pay-for-play program by honoring existing "commitments" to players without assuming new ones. When his role in the scandal became public, Governor Clements apologized, and admitted that his decision to continue payments to existing players had been an error in judgment. Facing an avalanche of negative press and even calls for his impeachment, Clements could only hunker down and endure.

The newly reelected governor also found himself besieged in his early second-term budget battle with the legislature. Caught between the need to increase revenues to maintain the state's basic functions, and a firm campaign pledge not to raise taxes, the Governor eventually agreed to a compromise $38 billion budget, with additional riders to raise $5.7 billion. Predictably, Texas Democrats were unappeased by the arrangement, while Republicans derided the compromise as a betrayal of a core campaign promise. It had been an inauspicious start to the last leg of Clements' political career. By the summer of 1987—barely six months into his term—his disapproval rating was at 68%.

Yet from this early nadir, Clements would come back to cement his legacy in the latter part of his second term. From education reform to prison construction, and from luring new industries to promoting tourism, Bill and Rita Clements steadily built a record of accomplishments. Clements dedicated himself to winning a proposed national particle collider for Texas (the project later fell through when federal funding for the project was rescinded) and renovating the Texas State Capitol. He used special sessions to reform workers compensation laws, led the consolidation of state criminal justice agencies under the umbrella of a new Texas Department of Criminal Justice, and established the Texas Department of Transportation. During his tenure, the economy righted itself and diversified considerably, reducing the odds that an oil slump would send Texas into another 1980s-style recession. All the while, his appointments of Republicans to key posts throughout state government continued steadily.

Fairly or not, the Ponygate scandal ensured that Bill Clements would never win another election. But for all of its embarrassment, rancor and difficulty, his second and final term was a policy success, and a crucial political building block for Republicans. And even though a Democrat—Ann Richards—succeeded him, when Bill Clements left office for the last time at the end of 1990, both Texas and the state Republican Party were poised to thrive.

A TEXAS LEGACY

Outtake from campaign photo shoot, 1978.